Compiled by

Maggie Forest

This article is the result of my research into the forms of marriage in Northern Europe, specifically Scandinavia and England, during the High Middle Ages – a topic that came up as my man and I were planning our own marriage. It is an attempt to collect and make available the information we found in that process, in the hope that it may be interesting and useful to others. It is not a scholarly work as such; it is subject to my own preferences and interests.

Throughout time, the marriage act has been shaped through two different

approaches. The marriage joins two people together – but it also joins

their families and their property. It is a fundamental economic vehicle for

our society. Not surprising then that it also took on a religious aspect;

the higher spirit must bless something so fundamental. Over time then, the

ceremonies surrounding a marriage has come to consist of a somewhat confusing

mix of legal and religious

components.

At this time, 1250-1450, the Christian Church had dominion in the countries of the North. The outward signs of the old faiths, if not all the beliefs, had all but disappeared from public view, and other faiths, such as the Jews and Gypsies, were still alien to most native Northerners even when not viewed with outright hatred.

I will therefore concentrate on the Catholic wedding. For those interested in recreating a medieval wedding but of Protestant faith mundanely, there are a few compromises that have to be made, even providing you can find a celebrant who is open minded. The first Anglican Book of Common Prayer and indeed most of the very first prayer books in protestant Europe were very close to their Catholic predecessors, particularly in the celebration of marriage, since this was so fundamentally rooted in civil tradition, which did not disappear with the advent of the Reformation.

Much depends on what the celebrant and the couple feel comfortable with. It might be hard for example to reconcile the attitudes towards women expressed in the rituals with modern sensibilities. Obedience and meekness are required by the bride, while the groom is charged with honouring and protecting his new wife. However, the church’s insistence upon mutual consent and male fidelity were innovations that changed the situation of the bride considerably from earlier times. At least theoretically the bride had an opportunity to refuse the marriage, and male infidelity, while societally accepted, was a sin in the eyes of the church.

The ceremony and customs surrounding the marriage by the High Middle Ages sprang not only from the Church but were rooted in ancient beliefs and traditions. The transfer of property inherent in a marriage meant that a large body of civil and legal custom had grown up to control it.

The Church, considering the marriage to be a holy sacrament, actively pursued a Christian ownership of the marriage rites, and also of the legal surrounding. This was however a very slow process. The early Church also understood the need to avoid alienating their congregation. Such traditions and rituals that were not offensive to the Church were incorporated into the endorsed wedding, and in some cases adopted outright [1].

This was not a new thing; the marriage ceremony in the early Catholic Church sprang from the pagan Roman wedding, and there are many possible influences also from the Germanic traditions, possibly absorbed during the Visigothic reign of Rome.

The result, by the Middle Ages, was that while most of Europe acknowledged the Roman Church, the Rites used in the Mass varied from location to location depending on local traditions and ancient beliefs.

Northern Europe, with the exception of the Celtic areas (which had been Christian for a very long time indeed by the High Middle Ages), was predominately Germanic territory. The legal and ceremonial components of the marriage were similar all over the area, although the Continental people, who were converted earlier through their history as Roman provinces, were closer to the Roman rites than England and the Nordic Countries.

In the generic sense, a marriage in pre-Christian times was the fulfillment of a legal contract. This contract was negotiated between the groom and the guardian of the bride, usually her father but not necessarily.

Once the contract was agreed, the pagan marriage then consisted of the following components:

When the contract was drawn up and agreed on, the betrothal ceremony took place. This was when the terms were confirmed and the intent of a marriage stated. Although the bride had not yet been handed over the groom paid the bridal price at this point, and consequently breaking the contract after the betrothal carried heavy penalties.

The actual wedding usually took place in the home of the groom. It would be in connection with a feast put on by the groom and his family. Her father and other members of her family would take the bride there, and the groom would call for the ceremony to start. The father then handed over the bride in the presence of witnesses.

The land laws of Västergötland in Sweden tell us that the requisite formula for a legal wedding was ‘I give to you my daughter’. The groom accepted the bride’s hand from her father, and the feast continued.

The final component was the ‘bedding’, when the newlyweds went to bed in the presence of witnesses. Once the couple had got into bed, the guests left. This was a confirmation that they were likely to have slept together – a necessity for the wedding to be legally recognized. It is probable that there was some religious ritual in conjunction with the bedding – it would seem likely that forces of fertility and prosperity were called on to bless the new couple.

If the marriage was unsuccessful, the option of divorce existed. We read in the Norse sagas that the process was fairly simple, although it appears not to have been taken lightly. Tacitus on the other hand suggests that it was quite commonplace. Whether this reflects differences in attitudes between the observers (the Sagas were written down in Christian times, when a divorce was virtually unthinkable) or between the peoples described (Viking Age Iceland/Norway in the Sagas, the much earlier Continental Germanic Tribes in Tacitus) is difficult to know. Suffice it to say that divorce was available and more or less accepted.

The divorce was an early casualty of the advent of Christianity in these lands, although particularly early on the Church was forced to accept that marriages might be annulled. Another was the concubinage. The Germanic peoples were traditionally polygamous, and the desire of the Church to make men marry their concubines is evident in some customs of the Christian marriage.

The church fought particularly had to gain control of the marriage and those other rituals that it considered sacraments. That it was a hard battle is shown in that right up to the 13th and 14th Centuries, the civil "land laws" of the North could still recognize a marriage that had not been consecrated by the Church.

In 1216, a letter from Pope Innocentius III to the Archbishop of Uppsala discusses what should be done about people who have entered into a ‘secret marriage’ without the blessing of the church. In fact, it was not until the Council of Trent, 1545-63 that the Church believed it had enough power to enforce a decree that purely civil weddings would not be recognized. The old viewpoint that a marriage was a civil contract between two families prevailed.

Little by little, however, the Church exerted its influence on the different parts of the process, so that by the 14th Century a marriage could consist of several, curiously mixed civilian and Christian elements:

The contract for marriage was still very much a family affair, regulating the respective advantages of the union. The negotiation of the contract usually took place between the groom and the bride’s father or other guardian. He was known in Scandinavia as the ‘giftasman’, the ‘giving man’, or as the ‘bruttoge’ in the Gothic (Gotlandic) language; in Latin documents as the ‘propinquus’.

Roman law, the basis of most medieval laws, specified that:

"A written marriage contract shall be based upon a written agreement providing the wife's marriage portion; and it shall be made before three credible witnesses according to the new decrees auspiciously prescribed by us. The man on his part agreeing by it continually to protect and preserve undiminished the wife's marriage portion, and also such additions as he may naturally make thereto in augmentation thereof; and it shall be recorded in the agreement made on that in case there are no children, one-fourth part thereof shall be secured in settlement."[2]

The word ‘dowry’ is used with many meanings in sources. It usually denotes something being given in return for the marriage; given either by the groom and the bride. Usually the groom would ‘pay’ a sum of money or give jewellery or more substantial items, including land. The bride would bring household goods to her new home: pots, pans, textiles and servants.

Originally, the groom and his family had to pay a bridal price to the bride’s family. This pagan custom continued into Christian times, and the price paid could be quite substantial. The idea of the bride being bought can be felt to be offensive to modern sensibilities, however it does show the value placed upon a wife in a time when every life could be bought.

The prospective groom also had to provide a substantial gift to the bride herself. This was her marriage portion mentioned in the Roman Law, the ‘Dos’, or ‘dotem’ – her dowry. It would ensure that whatever happened, she had some means of her own to support herself.

In the last years of the 10th century, in southern Burgundy, a certain Ulric was betrothed to Ermengarde. Upon their betrothal, he made the traditional endowment to his future wife. Shrewdly, he made sure that the gift would not be questioned. With so many noble witnesses signing this document, they were unlikely to forget the endowment. If nonetheless attempting to steal back the property, the challenger would have to pay a fine that would increase with the value of the original gift. Ermengarde would be assured of her property.

The authority of believing men stands adequately strengthened by what ancient custom the law of both Old and New Testament shows and by confirmation from the teachings of the Holy Spirit through Moses on marriage between man and woman, especially when It says: "Wherefore a man will leave his father and mother and adhere to his wife, and they will be two in one flesh." [Gen., ii. 24]; and indissolubly, supported by the divine word saying: "What God has joined, let man not separate" [Matt., xix. 6; Marc., x. 9] Even our Lord, who became a man and was the maker of men, was willing to attend weddings to confirm that marriage itself was holy and full of authority, in order that this pact and that joining might be held valid for ever by all Christians.

THEREFORE I Ulric, following such great authority, led by the counsel and admonitions of my friends, and assisted by celestial piety, seek a matrimonial partnership. For love of this and according to ancient practice, I give thee, my dearest and most beloved betrothed sponsa Ermengarde, by authority of this endowment ("sponsalicium") everything of mine within the pagus of Macon, that is, . And I give thee in the pagus of Lyons ... all things listed above, just as they are written, I cede, hand over and transfer in perpetuity to thee, my beloved sponsa Ermengarde to have, to sell, to give or to lease out and to do whatever you wish in them or with the same things at your free will. But should I or any of my heirs wish to come and say anything against this endowment gift ("sponsalicium donum") or in any way disturb it -- and I do not believe this will happen -- then he is not to obtain what he seeks to recall but should be liable for double the improved value of the whole property, and the present grant shall remain firm, together with the supporting stipulation.

Done in the city of Macon. Sign of Ulric, who asked for this endowment ("dotem") and gift to be made and affirmed. Sign of Rather his brother, who consented. [15 names of signers follow, then] Sign of Count Otto. Sign of Countess Ermentrude[3]. Sign of Guy. Given by the hand of Rodulf the priest on the fourth of the nones of September, in the 3rd indiction, the 8th year of the reign of King Hugh.[4]

Later in medieval times, the bride’s family had to come up with a substantial amount of money for their daughters’ dowry, payable to the groom. The bridal price had been replaced with a purchase of the groom. Why this happened may be debated; it has been argued that with repeated outbreaks of plague and wars, the number of available men was reduced and a husband therefore became a rare commodity that had to be bought. Possibly it was simply a reflection of the deteriorating position of women in European society.

The couple needed to be able to support themselves and any children they would have. It normally fell to the groom or his family to supply them with a suitable home and income in addition to whatever the bride brought to the marriage.

Still there was the future security of the wife to consider. If her husband died, would she inherit? In Flanders, for example, the wife would apparently inherit anything her husband left behind, even property he had inherited from previous marriages. Often, however, the wife’s inheritance was very limited or nothing; her husband’s heir would be his children or if he had none, his family.

To this end the bride was usually given a portion of her husband’s estates. This was sometimes known as the dowry (cf. Dowager – a widow living off her dowry), sometimes as the morning gift. In England, the dowry was normally a third of the groom’s estates, either at the time of giving or at the time of his death. In fact, the law came to state that had nothing been specified at the time of the wedding, the widow was entitled to a third of her husband’s estate at the time of his death. In Scandinavia there appears to have been no legal requirements involved, and no customary size of the morning gift. For practical reasons, however, it would have to be enough to support her in the case of her husband’s death or as much as he could afford to give her towards that end.

So, for a medieval wedding, three gifts exchanged hands. The bride’s family purchased a groom for her, the groom’s family in turn provided them with a living, and the groom ensured the bride’s future by specifying a portion of his property for her use after his death, or by giving it to her outright. In addition there was naturally a donation to the Church, in the form of a gift to the priest who performed the service.

The bride’s dowry or morning gift was specified as part of the wedding ceremony. It could be done either symbolically, by placing coins on the bible along with the ring, or more formally. There were many ways to do this; by a reading of an endowment, placing of gifts on a shield, or the very old ceremony of land gifting; placing a sod of earth in the cloak of the recipient. The words of the ring gifting, ‘with this gift I thee endow…’ refer to that formal handing over of the wife’s dowry.

The endowment had to be written and witnessed like any other legal charter to make it valid. These legal documents took on a formulaic style very early on. By the 12th Century there were contractual style guides. Naturally, they also dealt with the proper form for endowments, or dowries.

The standard endowment included a short treatise on the reason for it; the value of marriage and some pious observation. The scribe then gets down to business, specifying the endowment, the recipient, and any recourse in case of dispute. This document was then signed by the person making the endowment, any other people who had an influence over it (such as family members who signed their approval), witnesses and whenever possible persons of authority, who were after all the likely judges in case of a dispute.[5]

One ‘style guide’ is the Aurea Gemma (Gallica). It was collated in the 12-13th Centuries, and contains models for all manner of contracts. It has two examples of dowry contracts.

First:

[2.30] Since human fragility must be supported by the manifold help of remedies, the Maker of the world, who is ignorant of nothing in the nature of things, instituted holy matrimony in Paradise, saying "The two were once one in the flesh and for this sake man shall leave his father and mother and cleave to his wife", and at Cana Galilee the Lord consecrated a marriage by his presence.

[2.31] Thus relying on such a great authority, I, N., have joined this woman N. to myself in a nuptial bond in the hope of propagating offspring. But because the acts of mortals suffer the wound of oblivion, unless they are bound up by written records and they are defended from the annihilation of oblivion by the support of these records, it has been salutarily provided that we should transmit to posterity a written memorial of things done, lest any occasion of controversy can arise or the exception of a fraudulent advocate. Thus we have taken care to transmit in written form a summary of a thing done to the memory of posterity...

[2.32] We have also thought it worthwhile to insert in this charter the names of those witnesses who were present for this action, that truth annexed by the testimony of many may easily explode the fallacy of contemptuous persons. At the end should be noted the year of the Word's incarnation and the indiction and the regnal year of the king or emperor in whose realm this was done.

And the second:

[3b.83] By a profound counsel it should be decreed that the sacrament of marriage has been commended to us through wise men. For when God formed woman from the side of the first man, he thus marvelously prefigured the identity of the marriage bond and those who had been fictively shaped as two were joined together in one body.

[3b.84] I, P. completing a marital relationship, taking M. as a wife and by an institution of the church granting myself to her as husband, wish it to by know to all by the present page, what I endow to her to have in dowry. For it is right for her to enjoy nuptial payments, who will sustain the burden of generation in the sufferings of childbirth.1 Thus I grant to her as dowry the village which is located near Gurk, with fisheries and other things. So that the transaction of my donation shall remain perpetually firm and undisturbed, I establish B. and C. as warrantors in good covenant. Nor should it be omitted that the aforesaid village owes to the lord king once a year the service of one horse, to be returned to the lord or lady of the village after its labor is completed. But if the king had claimed or retained one half or some other part <of the service>, the lord of the village, until it be restored, should not render service of a horse.

This ceremony, a blend of the original betrothal ceremony, the civil wedding, and some relatively superficial Christian influences, took place in the home of the groom. The groom was the host of this event, except in later times when the bride’s family normally hosted wedding festivities. Depending on the specific words spoken, this could be a betrothal or a civil wedding.

The act took place during the feast. Her father or ‘giftasman’ brought the bride there. The groom called the party to order and asked the ‘giftasman’ to conduct the ceremony. This was very simple. In the presence of the witnesses, the bride’s hand was given to the groom, with some kind of formula spoken by the parties during this handfasting. In earlier times, the old formula ‘I give to thee my daughter’ was sufficient to make a wedding, although a ‘in the name of the Lord’ was added onto the end of it.

In later time, a declaration of consent was introduced. If it was spoken in present tense it constituted a legal wedding which would be recognized as such by civil authorities, if not by the church. For a betrothal, this declaration of consent was spoken in future tense, and as a betrothal the Church recognized it although in later times they would insist on a priest being present.

Pope Alexander III (elevated in 1159) codified the difference between a ‘sponsalia de futuro’ and a ‘sponsalia de presenti’, stating that in some cases the first could be dissolved, as long as consummation had not taken place. In 1234 Gregory IX again brought up the issue. On the whole a confusion of the betrothal/civil wedding/fasting was consistent throughout the period, something which makes it difficult at times to reconcile what components actually constituted a wedding in the eyes of the Church and the Civil authorities respectively. There are enough court records to show that the contemporary authorities had enough trouble sorting it all out.

In the Scanian City law, it is stated that when a man ‘fasts’ a woman to himself, he should do so in the presence of ‘a priest and other good men and women’. This does not mean that the priest conducted the ceremony, merely that the priest was considered a good reliable witness for such an important legal ceremony. A Norwegian procedure from 1341 is similar.

After the declaration, the feast continued. Depending on the place and time, the couple might begin cohabitation at this point, although the church required abstinence until the wedding had been consecrated in church. Fines were specified for those who broke this rule as late as 1417 in the Arboga concilium.

Only one of the Swedish land laws makes the church wedding obligatory for a legal marriage, however the betrothal was not necessary either as long as the church ceremony had taken place. In other words, either the civil wedding or the church wedding had to have taken place for the marriage to be legally recognised. The church, eventually refusing to accept these ‘clandestine’ or civil marriages [6], nevertheless continued to have to live with the reality of them. It was a slow process for the church to change popular view of the marriage as a purely civil matter.

By the late 14th Century we seem to have reached the point where at least most couples of some standing did have a church ceremony before consummating their marriage. Largely this was achieved by the Church influencing the civil laws on inheritance; to be a legitimate heir now required the parents to have married in ‘the face of the congregation’ (unless a dispensation had been specifically granted for the clandestine marriage).

By the 15th Century, the Church had managed to exert its authority over the marriage process, right down to the betrothal. Where before the Church had accepted the civil betrothal on condition that the wedding itself was done in church, ‘clandestine’ betrothals (without the presence of a priest) were now to be considered illegal and the Bishops were ordered to enforce this. A sponsalia de futuro was not to be entered into without the presence of a priest. Nor was the sponsalia de presenti to be entered unless at the church door.

While the church insisted on marriage being a sacrament and that it should be done in church, with something of a leap of logic it was also a civil matter and therefore didn’t take place in church, but outside it. The actual wedding ceremony was done in the porch or on the stairs of the church. If it was a large church it generally had a specific ‘bridal door’ where weddings took place. Once the couple had been pronounced man and wife, the whole party moved inside the church where the marriage was blessed and the newlyweds received Holy Communion.

Before they could get married, however, the couple’s suitability had to be established.

One of the things the Church brought with it to the North was the confusing and somewhat constricting rule system for who could marry whom. The old Germanic laws proscribed that one could not marry someone who was immediately related; the Church proscribed first allowed level of kinship as the seventh. Worse still was that the Church not only counted kinship by blood but also by spirit. A woman could not marry her godfather, a man who was a joint godparent with her, nor the widower of the godmother of her child.

In smaller isolated communities this strict reckoning of kinship became a real problem, and the Church was forced on several occasions to give dispensations to such areas. Similar problems happened in the noble classes that were persistently intermarrying. Long term the policy became unworkable, and the Church ended up having to revise its stance.

With so many and confusing restrictions in place, it was hard to know who could be married and who couldn’t. With the traditional system of concubinage and divorce (unacceptable in the eyes of the Church) added to the mix, the situation of the couple intending to marry needed to be investigated before the wedding. This investigation was the responsibility of the Bishop, and by delegation the parish priest who would marry the couple.

The system of banns was developed to help in these investigations. By publishing the names of the couple those who knew their background had an opportunity to speak up, preventing sin. If the couple lived in different parishes, the banns naturally had to be read in both.

At the fourth Lateran Council (in 1215), the banns were made compulsory for a marriage to take place in church. The priest was not allowed to perform the service without them, unless a specific dispensation had been given for a ‘secret’ wedding. Several of the land laws of Scandinavia (written down in the 13th and 14th Century) also regulate the reading of the Banns.

In the Södermanna law, it is stated that once the bann is read the priest must inquire who is the legal ‘giftasman’ for the bride. This was to make sure that the correct person gave his consent to the marriage at the ceremony. The laws often also make it clear that the banns are to be read after the betrothal, or ‘fasting’. In the Östermanna and Västmanna laws, the betrothal is compulsory. Interestingly, they do not recognize or require a purely civil wedding before the church ceremony.

Canonic law stated that if a person had heard the banns being published, and knew of a hindrance to the wedding yet did not speak up, then he/she was guilty of sin and had to pay fines to the bishop. Moreover, the couple was often permitted to stay married (with some exceptions depending on the severity of the hindrance). The banns had to be read three times on feast days or other times where the whole congregation was likely to hear it, and there was a last opportunity to speak at the wedding.

The formula for the banns was something like this:

"I PUBLISH the Banns of Marriage between [groom] and [bride]. If any know cause, or just impediment, why these two should not be joined together in holy Matrimony, ye are now to declare it. This is the first [second, or third] time of asking".

The church, while attempting to unify the protocol of worship throughout its domain, also acknowledged that in some cases there had to be differences based on geography. This was particularly the case in the wedding ceremony, since much of the ritual had to be conducted by the couple, and therefore in the vernacular language, anyway [7]. These rites developed in different places, of which many still exist.

The most influential Missal in the North appears to be the Sarum Rite. Developed for use in the south of England, it had a strong influence on the Nordic rituals. Other extant Missale from this time include the Lund, Roskilde, Uppsala and Nidaros Rites from the Nordic countries, the Hereford and York Rites from England, the Toledo ritual from Spain, etc.

The influence of the Sarum Rite was not limited to geography; even today the English Catholic Rite follows it very closely, and when the Anglican Church was formed their first Book of Common Prayer was, with a few exceptions, a fairly straight translation of the Missal. After some changes back and forth, the BCP of 1641 remained close to its Catholic roots, particularly in the sections concerning the Marriage. This in turn has influenced many of today’s Protestant churches, and so the ceremony of the Medieval Nuptial Mass continues to this day.

The ceremony was, as stated previously, split between the church porch and the inside. First, the couple would come to the porch, separately. It was common for the bride and groom to be accompanied by friends, who could be carrying banners, swords, flowers or other symbolic items. Musicians, who could be rowdy enough for the church to complain about their undignified and noisy progress, often led the bride to the ceremony. She would be wearing her best clothes, perhaps made for the occasion, and she may or may not have had her hair covered; this was one of the few times a woman might wear her hair loose. If she was not a virgin, previously unmarried, the Sarum Rite states she should be wearing gloves, presumably as a sign of her maturity. She did not, as a general rule, wear white.

In later times, churches began providing a crown for virgin brides. The bridal crown was an old tradition in the Christian church, as can be seen by the Pope’s letter to the Bulgars (see appendix C). It was a novelty in the North, however, and seems to have become very popular towards the end of the 16th century.

The oldest extant bridal crown in Sweden is dated 1597, and comes from Skepparslöv, near Kristianstad in Sweden.

Once at the church, the bride would stand on the left of the groom. In some areas her family would stand to the left of the area, the groom’s family on the right. In other areas, the division was by gender; the women on the left and men on the right, just as they sat inside the church.

The priest would then welcome the couple and speak to them of marriage and how they should conduct themselves. He would also, for the last time, publish the banns, in the familiar form; "let him speak now or forever hold his peace." In the event that someone did speak up, the wedding had to be stopped until the claim could be investigated. This was clearly pointed out in the rite itself, so that there would be no (further) confusion on the day.[8]

Once the wedding was going ahead, the first item was, naturally, the declaration of consent. There is much to suggest that this part had grown out of the betrothal ceremony; the parties are asked if they will have each other and answer in the future tense. It was a quite necessary part of the ritual that the couple declares their consent to the marriage before it went ahead; the church insisted on mutual consent for a wedding to be legal.

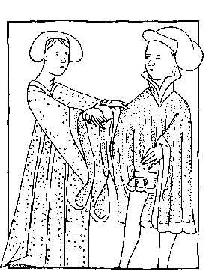

Next the oldest part of the ritual happens; the ‘gift’, the handing over of the woman from her family to the husband. This can take the symbolic form of her father handing her to the priest who gives her to the man, or directly to the new husband. It usually involved physically taking her hand and placing it in the hand of the recipient. Sometimes a formula was spoken as part of the handing over. In one of the versions of the Sarum Rite the formula is written down as "Ego in nomine domini eam tibi trado": I give her to you in the name of the Lord (cf. the betrothal ceremony).

Once their consent to marry has been established, they pledge their oaths. This constituted the marriage from a legal standpoint. They were now speaking in the present tense, declaring their union in some version of ‘I take thee to be my husband/wife’. Depending on place and time, both or just the man made the vows. The wording differed in the rites, particularly as to what each of them promised, but also how they did it.

The words used in the Sarum ritual are:

"I N. take thee N. to my wedded wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, and in health, to love and to cherish, ‘til death us departe: according to God’s holy ordinance and if the holy Church it will ordain: And thereto I plight thee my troth."

The words ‘if the holy Church it will ordain’ make it appear that this might be in question. However, for the wedding to happen ‘in facie ecclesiae’, the legitimacy of the marriage would already have been established. This then suggests that this is also a remnant from either a betrothal ceremony or from an intermediate ceremony which was still a completely civil affair, but in which the church was attempting to insinuate its influence. Tellingly, the Anglican service dropped this caveat.

The vows are then followed by the physical confirmation of their spoken vows; the ring or rings, and possibly the handing over or declaration of the dowry.

The dowry would be identified; symbolically, coins of gold and silver were placed on the bible along with the ring. In later times, this was in fact all that remained of the endowment. Earlier the endowment, if there were one, would have been shown or read out.

If the couple were of the noble class, the bride might be given land for her dowry. If in fact the woman received land for her dowry, the York rite and one or two of the surviving Sarum rites specify that she would fall ‘at the feet of her husband’ and kiss them in gratitude. This is also the case in the fragmentary Lund ritual.

The way the ring is placed on the bride’s finger also varies across different countries.

The English rites only specified giving a ring to the bride. Other countries’ traditions included an exchange of rings, and in some places the priest placed the ring on the bride’s finger.

The Sarum rite says to place the ring over first the thumb, then the second, third and fourth finger as the words ‘in the name of the father, the son, and the holy ghost, amen’ are spoken. The Swedish Uppsala rite leaves the ring on the third finger, at the mention of the Holy Ghost.

Which hand the ring was worn on also varies. It was the custom for the English Catholics to wear the wedding band on the right hand right up to the 18th Century. In other parts of Europe it was worn on the left hand. In some countries it was worn on the third, not the fourth finger.

Then comes the ‘handfasting’. The priest joins the couple’s right hands, wraps his stole around them, places his own right hand over them, and declares them to be married.

This handfasting, the symbolic joining of the hands is an ancient tradition going back past the advent of Christianity in Northern Europe. Before Christianity and the stole, the hands would be wrapped in a mantle, presumably that of her husband. Once the Church became involved, the symbolic binding of the couple by the power of the Church was neatly demonstrated by this simple act. This scene is encountered again and again in medieval art throughout Europe.

Additionally, the apocryphal book of Tobias, dated to the 2nd Century BC appears to have had a strong influence on the medieval wedding (see the Bride’s Blessing, below). In it, Raguel called Sarah to himself, and placing his daughter’s right hand in Tobias’ right hand, he said; "The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob be with you, and unite you and give you his blessing".[9] Not surprising then that this symbolic handfasting, already popular in Pagan times, was deemed ‘inoffensive’ and retained in the Christian ritual.

The words chosen to declare the marriage vary over time. The Catholic rites generally had the priest stating (in Latin) that he, personally, declared them married in the name of the father etc. This was seen as somewhat unfortunate, since it could easily be misinterpreted. Both the Catholic and Protestant churches have moved away from this wording.

This was the end of the actual wedding. The couple was now united in wedlock, husband and wife in ‘the face of the congregation’. The legal requirements had been met, and the only thing now missing was the act of blessing by the Church.

By the Middle Ages it was customary, indeed required, that the newlyweds receive communion. This had to be done at a mass, and so it was natural that there were special blessings said over the new couple. The nuptial mass developed as a result. It didn’t have to be said on the same day as the wedding itself and in many cases couldn’t; there were times of the year when the full ritual wasn’t allowed, notably Christmas and Easter. However, normally the wedding party proceeded into the church for the nuptial mass immediately after the wedding itself.

They did this in procession, led by the newlyweds who in some areas carried lit candles in their hands. There is some evidence that they put money underneath the candle when they placed it in its allotted holder at the altar.[10]

The women usually sat on the left side of the church, the men on the right. The bride and groom proceeded to the altar while the ministers or clerks sang, and then either the ‘Beati Omnes’ or the ‘Deus Meseratur Nostri’ was sung.

Then the bride was blessed under the ‘Pall’. This was a (silken) cloth, carried by four ‘unmarried persons’ (possibly two male, two female) and held over the couple or at least the bride. They were either kneeling or lying prone before the altar as this happened; the Pall had to cover the bride completely but only the shoulders of the groom, which suggests they were lying head to head.

The Bride’s Blessing was only allowed if the woman was within childbearing age and only once in her life. If she had been married and blessed previously, she was denied it. She was however allowed it if she was ‘corrupta’, i.e. had already had sexual intercourse with a man.

The Bride’s Blessing can be traced back to the Pagan Roman view of the wedding as the preparation of the bride for her new life as a wife. The ceremony then focused very much on her, as opposed to the couple. The age of this part of the ceremony is testified to in the consistent references to Old Testament scenes and role models. In the Middle Ages the couple was blessed as well, once the Bride’s Blessing had been said.

The mass then continued with the gospel and sermon, and so on. However, there was an option of reading a special text in place of the sermon in the Sarum Rite. At the end of the mass the couple then received Holy Communion. Ordinary people only received communion at Easter, which time was forbidden for weddings. This exceptional favour enhanced the status of the wedding as a holy sacrament.

This also means that the couple had to fast before the wedding to be pure at the communion. This probably explains the fact that the wedding feast afterwards was called the ‘wedding breakfast’, regardless of what time it happened.

The kiss of peace was also given to the newlyweds specifically. The priest gave it to the groom, either directly or through the ‘paxboard’. The groom then kissed the bride. Still to this day the traditional ‘you may kiss the bride’ remains in most ceremonies.

The bedding was retained, despite its rather lewd connotations, because of the importance of consummation to the legality of marriage. This did remain a disputed point; if there was consent, argued some, the marriage was legal even if it was not consummated. If conversely there was consummation without consent – in other words rape – the marriage should not be legal.

The highest-ranking person there led the couple to the marital bed in solemn procession. Again, there is some evidence that candles were used symbolically in the ceremonial bedding; the new Protestant Church of Sweden stated that candles were not to be used in church, for brides or for the bedding; candles being seen as ‘papist’ symbols.

The church condoned the Priest blessing the marital bed, but refused to acknowledge the Bedding as an official event. However, the first Protestant prayer book of Sweden does specify a suitable blessing for the occasion:[11]

"In the Bride’s house:"

"Oh, Almighty Eternal God, give thy blessing to this bridal house, that all these who live herein may be in peace and follow thy will and live in thy love to a good age. Through Christ our Lord. Amen."

"And this he speaks over them:"

"God Almighty bless your bodies and your souls, and let his blessing come over you as he blessed Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. God’s hand protect you, he sends his holy angel, who keeps you all your days, God Father and Son and the Holy Ghost, let his blessing come over you. Amen."

[1] "If, however, in any provinces, other laudable customs and ceremonies are in use besides the foregoing in the celebration of the Sacrament of Matrimony, the holy Council of Trent desires that they should be retained." (Full text)

[2] Full text. More information on Roman Law pertaining to Marriage can be found here.

[3] These are the signatures of the Count of Macon, his wife and son. These were the local authorities, and any disputes would be likely to end up before their court. To get the Count and his heir to sign the endowment was therefore a good way of ensuring justice; they would remember, or at least recognize, their signatures. The Countess would also make a good witness.

[4] Found in the Medieval Sourcebook: A Husband's Endowment Of His Future Wife On Their Betrothal.

[5] "And it should be known that charters are of little or no weight,

which are not strengthened by the seals of those persons, for whom it is

legal to have seals. Therefore, he who wishes to repress all calumny of malign

men, strengthens his charter with the seal of the bishop or the duke or the

count or the prince of that land."

Aurea Gemma <Gallica>

2.43-44 (Links broken)

[6] Medieval Sourcebook: Council Legislation on Marriage

[7] Strangely enough, the Uppsala Missal tells us that the whole ceremony was done in Latin, and that the Priest 'taught' the groom and bride the words they needed to speak, in other words they repeated what he said. Most countries however did at least the vows and the declaration of consent in the vernacular. (Carlsson. 'Jag giver dig min dotter'.)

[8] "At which daye of mariage yf any man doe allege any impediment why they maye not be coupled together in matrimonie; And will be bound, and sureties with hym, to the parties, or els put in a caution to the full value of suche charges as the persones to bee maried dooe susteyne to prove his allegacion: then the Solemnizacion muste bee diflerred, unto suche tyme as the trueth bee tried. Yf no impedimente bee alleged, then shall the Curate saye unto the man." (First Anglican Prayer book.)

[9] "Et apprehendens dexteram filiae, dextrae Tobiae tradidit, dicens: Deus Abraham et Deus Isaac et Deus Iacob vobiscum sit, et ipse coningat vos, impleatque benedictionem suam in vobis". (Vulgate)

[10] Carlsson: 'Jag giver dig min dotter', pp 14-15

[11] Translation from the first Swedish Prayerbook. See full text.

First Anglican Prayer book, 1549

Other versions of the Book of Common Prayer

First Swedish Protestant Prayer book (with a partial translation)

Letter from Pope Nicholas to the Bulgars concerning marriage ceremonies

A Royal Wedding in Landshuter Hochzeit 1475

The Catholic Encyclopedia

(This is an essential site, discussing the history and background for many

of the elements of medieval beliefs and rituals)

A resource for catholic liturgy

The SCA Arts & Sciences pages are always useful

The Rialto (Rec.org.sca) gets archived and sorted by Marc Harris.

There is also a site devoted to

Medieval Marriage

On this site there is another essay about medieval weddings, which I thoroughly

recommend.

There is much information on the World Wide Web, and it changes all the time. I would suggest that anyone doing research on the topic, or wanting to see what other people have come up with, go do a search on ‘medieval wedding’ using their favourite web search tool.

Lizzie Carlsson, ‘Jag Giver Dig Min Dotter II’, Institutet för Rättshistorisk forskning, Lund 1972

Ingvar Andersson, ‘Skånes historia’, P A Norstedt & Söners förlag, Stockholm 1974

Kulturens Årsbok, Lund 1993

Jennifer C. Ward, ‘English Noblewomen in the later Middle Ages’, Longman Group UK Ltd. 1992

Jennifer Ward, ‘Women of the English nobility and gentry 1066-1500’, Manchester University Press, 1995

Martha C. Howell, ‘The marriage exchange; property, social place, and gender in cities of the low countries, 1300-1550’, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1998

Joseph and Frances Gies, ‘Life in a Medieval City’, Harper & Row, New York 1969

Georges Duby, ‘ William Marshal, the flower of Chivalry’, Pantheon Books, New York 1986

Ed. Hugh Tait, ‘Seven Thousand years of Jewellery’, The Trustees of the British Museum, London 1986